An understated legacy

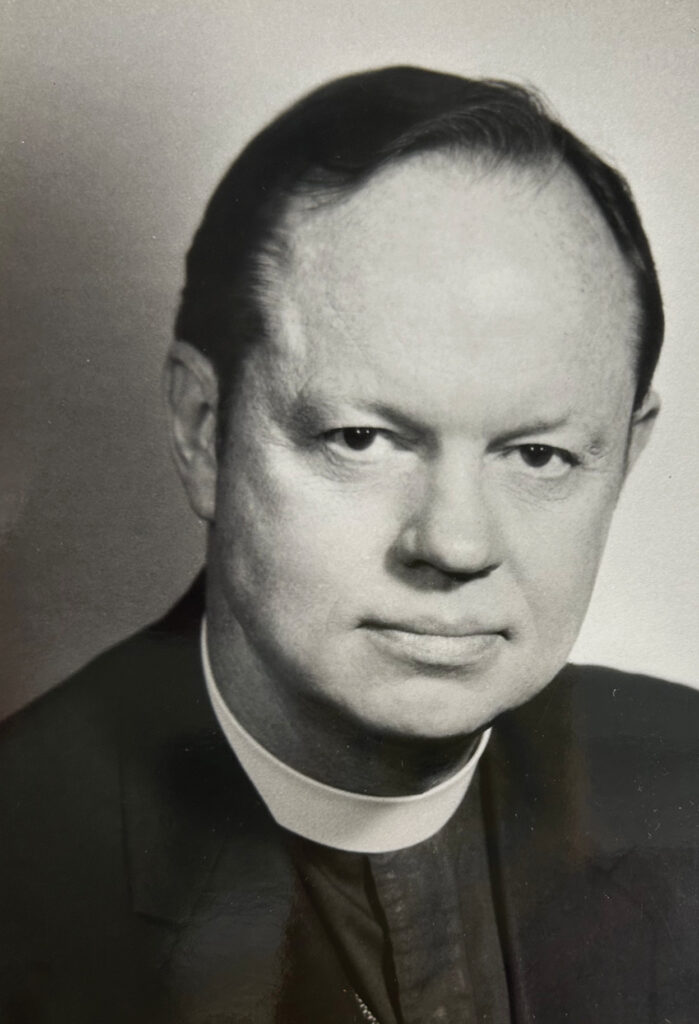

Bishop John Maury Allin and the Committee of Concern

by The Rt. Rev. Dr. Dorothy Sanders Wells

To borrow words from William Shakespeare and John Steinbeck, the summer of 1964 was the summer of Mississippi’s discontent.

The struggle for Civil Rights for black persons had escalated—and advocates and supporters from around the country had joined sympathetic Mississippians on the ground. Non-violent protests for access to places of public accommodation punctuated the hot summer of 1964—but the struggle for voting rights was at the forefront of the summer’s work, in a state in which voter literacy tests that even white citizens could not pass without assistance were implemented to prevent black persons from exercising the right to vote.

It was a summer in which James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner were killed near Philadelphia, Mississippi while working to dismantle those discriminatory voting practices.

It was a summer during which reportedly more than 50 black churches—targeted as seats of Civil Rights organizing—were burned and bombed.

The response to the destruction of these black churches was the unprecedented establishment of the Committee of Concern, on September 9, 1964. This interfaith body—comprised of 23 white and black Christian ministers and a Jewish rabbi—was formed for the purpose of helping to raise money for the rebuilding of the churches, and was reportedly the first desegregated meeting of clergy to take place in the Baptist denomination’s state headquarters. Dr. William Penn Davis, President of the Mississippi Baptist Seminary, an institution founded by white Baptists for the education and formation of black Baptist ministers, was the first Chair of the Committee of Concern. Its goal, Davis said, was to allow persons of “goodwill” an opportunity to respond to the violence by cooperating to rebuild the worship sites. Many of the churches that had been destroyed were Baptist.

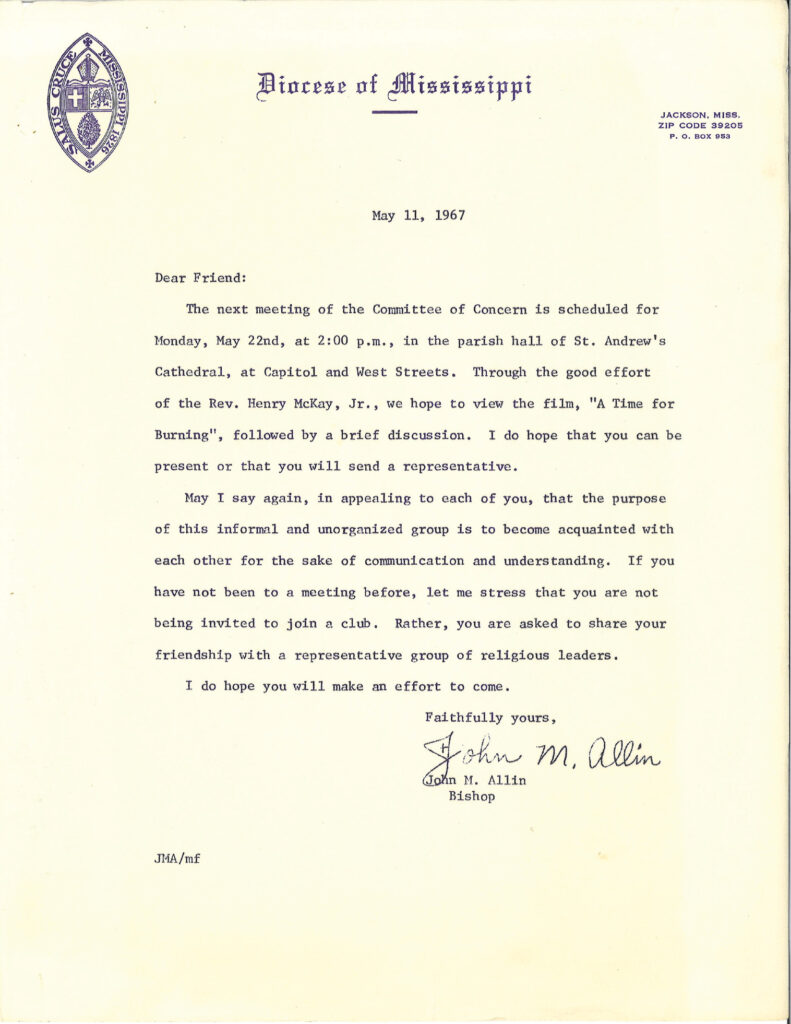

The Rt. Rev. John Allin, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Mississippi, was present at that first meeting of the Committee of Concern. Bishop Coadjutor Allin became one of the members—and part of the executive committee. Bishop Allin was named Chair of the Committee of Concern in September 1966. His work with the Committee of Concern has largely been untold—and overshadowed by the work of the Baptist Church in Mississippi.

Bishop Allin’s role on the executive committee of the Committee of Concern was reported to be much about fundraising. By early 1967, just 2 ½ years after its establishment, the Committee of Concern had contributed to the rebuilding of 42 of the churches. Oren Renick, biographer for Dr. William Penn Davis, reported that nearly $129,000 had been raised for the work. Despite the rebuilding effort having been criticized by segregationists, more than half of the funds raised reportedly came from Mississippians. In addition to the funds raised, teams of students from colleges, universities and seminaries around the country reportedly arrived to offer free labor for the rebuilding projects, working alongside teams from Mennonite Disaster Service and the Society of Friends (Quaker). A Jackson, Mississippi architectural firm contributed blueprints and designs for the churches, and a San Francisco landscape architect was said to have contributed landscape plans for all of the churches. The Baptist Program also reported that a number of Mississippi businesses contributed building materials and equipment. The contributions of labor and materials were estimated at more than $375,000.

Bishop Allin’s influence on the Committee of Concern is duly noted in the fact that he was invited to preach the dedicatory services for at least two of the rebuilt churches—Mt. Zion United Methodist Church, in Philadelphia, Mississippi, and Central Union Baptist Church. Both invitations are noteworthy. Mt. Zion United Methodist Church was burned on June 16, 1964—shortly after those three Civil Rights workers—Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner—had visited the church, encouraging its members to try to register to vote in spite of the perceived futility and threats of violence in doing so; the three men returned to the burned-down church to see the damage and to meet with church members on June 21, 1964, just before they would be killed. A memorial to the men has been erected on the site. Central Union Baptist Church, originally situated in Madison County, was burned on July 17, 1964, and is said to have been the first church rebuilt with the Committee of Concern’s assistance; it was rebuilt at a new site closer in Jackson. The Clarion Ledger reported that Bishop Allin preached the dedication of that new church site on January 24, 1965.

Bishop Allin’s work with the Committee of Concern, and the participation of The Episcopal Church in the National Council of Churches (NCC), were not without controversy within the Diocese. Some parishes objected, claiming that attracting new communicants would be difficult given the publicity surrounding our denomination’s role in the Civil Rights Movement. And, parishes threatened to withdraw financial support from the Diocese (See, The Sixth Bishop of Mississippi: A Study of the Times of John Maury Allin and the Episcopal Diocese of Mississippi) because of desegregation efforts. Bishop Allin remained steadfastly focused on the need for improved race relations and a study of poverty and missions to address that work.

Bishop Allin remained committed to the work of the Committee of Concern in large part because of the fact that he believed it would allow for greater communication between black and white persons in Mississippi. He was quoted as saying that the concept of communication had been missing—and that communication was key. Indeed, Bishop Allin recognized that communication is a powerful instrument to diminish fear and the violence that fear often begets.

By 1967, Bishop Allin, together with Catholic Bishop Joseph Brunini and United Methodist Bishop Edward Pendergrass, had called for the establishment of a biracial statewide commission “charged with the realization of a greater sense of unity and responsibility among all Mississippians.” And, by January 1968, 3½ years after that troubling summer of 1964, the Annual Council of the Episcopal Diocese of Mississippi passed a resolution denouncing the black church burnings and bombings, and calling for the establishment of a state Commission on Human Relations and investigation of law enforcement.

Although Bishop Allin would have claimed himself a traditionalist, many labeled him—because of his work in calling for improved race relations—as a liberal. Nonetheless, in spite of opposition, Bishop Allin went on, in 1973, to be elected the twenty-third Presiding Bishop of The Episcopal Church. He was elected to a Church that was already experiencing a decline in attendance: The Living Church reports (June 30, 2024 issue) that in the six years prior to his election, The Episcopal Church had “lost about 15 percent of its membership…after decades of steady growth.” And, during his tenure, the Church faced the controversial and divisive matters of women’s ordination (which he did oppose) and the 1979 adoption of a revised Book of Common Prayer. While either of those matters might have been all-consuming, Presiding Bishop Allin continued a focus on justice. Keeping an eye on the need to seek and serve the welfare of all of God’s people, Presiding Bishop Allin, according to The Episcopal Church archives, single handedly persuaded a reluctant Executive Council to launch a national fundraising initiative in support of programs to alleviate poverty and injustice, clergy education, and congregational development. “Venture in Mission” (VIM) was a major fundraising success that greatly expanded social justice programs and ministry during the 1970s. VIM was a tremendous success in the local dioceses, far outreaching its $100 million goal and funding hundreds of still-active Church programs and community non-profits. (msepiscopalian.com/allin)

Bishop Allin is a rich part of the history of the Episcopal Diocese of Mississippi—and he proved himself willing to take strong and controversial stands that have continued to shape not only our Diocese and state, but all of The Episcopal Church. Mark Duffy, former canonical archivist and director of the Archives of The Episcopal Church, comments, “John Allin’s ministry was rooted in a generous understanding of mission in service to others as the central organizing force in the church’s life, and that theme is worth revisiting as we embark on a new examination of our capacity for reconciliation.” (livingchurch.org/news/archival-upgrade) As we lean more and more into what it means to love neighbor as ourselves and strive for becoming God’s beloved community, we are thankful for Presiding Bishop Allin and his witness—in Mississippi, and beyond.